Abstract

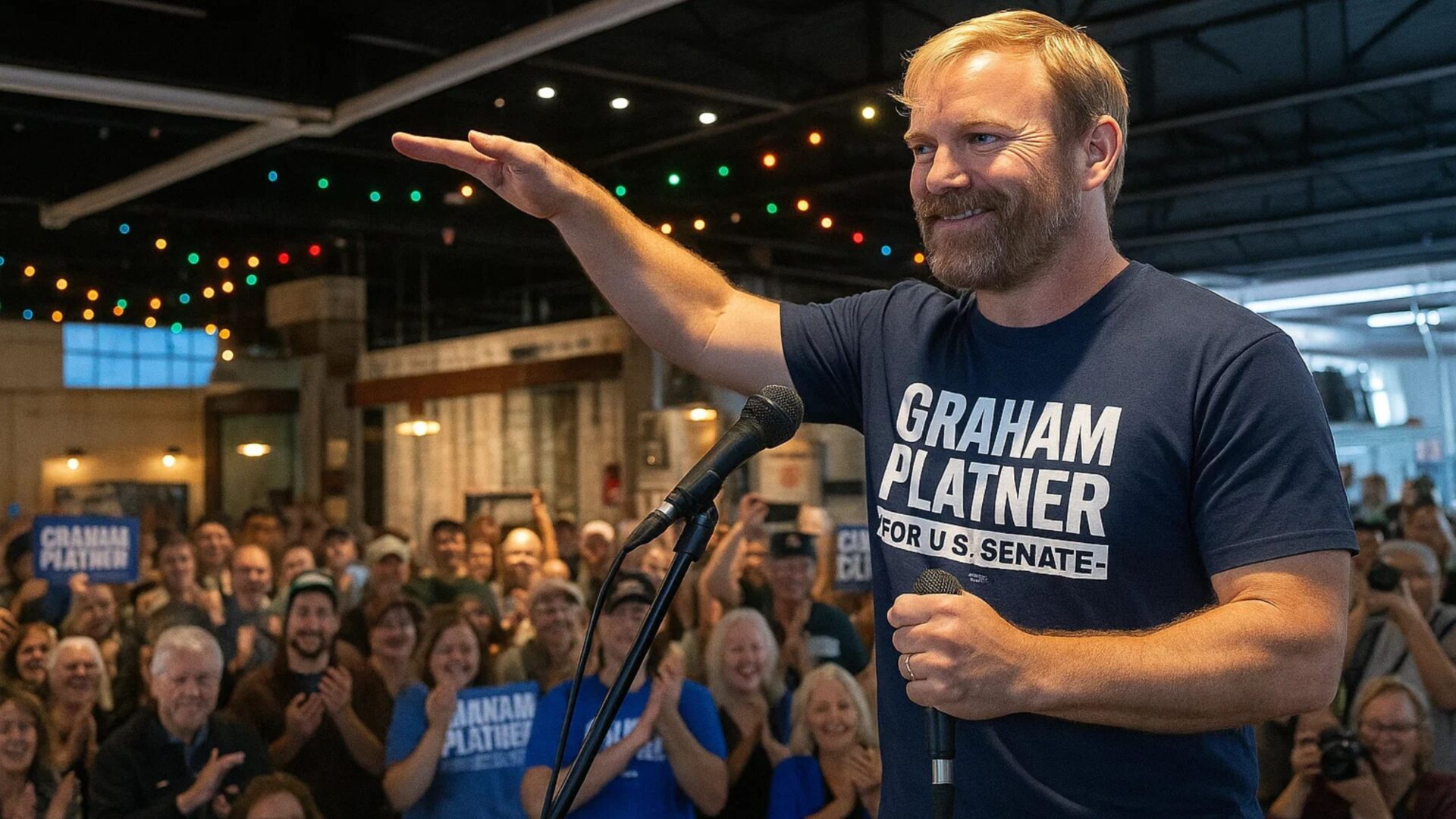

In an era of digital immediacy and algorithmic echo chambers, political adherence has become increasingly performative, tribal, and reactive. This paper explores the psychological underpinnings of political party loyalty, particularly in progressive and leftist movements, through the lens of identity theory, tribal psychology, and historical philosophy. We examine the emergence of digital influencers like Graham Platner (who is blamed for being a secret Nazi), who capitalize on cycles of disillusionment and reinvigoration within political parties.

Drawing on the works of Plato, Aristotle, Cicero, Nietzsche, Tocqueville, and modern social cognition theorists, it situates the modern ideological turbulence within a recurring historical rhythm: the rise, idealization, corruption, and fragmentation of movements. The study also considers the phenomenon of the digital prophet, typified by figures such as Graham Platner, who channel ideological fatigue into renewed fervor.

Ultimately, this work argues that modern digital partisanship is less a product of reasoned conviction than of existential longing—for belonging, clarity, and moral certainty in an age of perpetual flux.

Introduction: Digital Echoes of Ancient Warnings

Political philosopher and Roman statesman Cicero declared, “The welfare of the people is the highest law.” Yet he also warned that “the more laws, the less justice.”

From the beginning, political systems have wrestled with the tension between freedom and order, equality and responsibility.

Plato, in The Republic, warned that democracy, left unchecked, may degenerate into tyranny when the masses, “intoxicated by freedom,” submit to the will of persuasive demagogues who promise equality without discipline. Aristotle deepened this caution in Politics, noting that “a state aiming at equality must consider whether this means equality of wealth or equality of freedom.”

The anxiety is not ancient nostalgia—it is prophetic. Tocqueville, writing in Democracy in America (1835), foresaw that democracy might breed “an immense and tutelary power” which keeps citizens in perpetual childhood, willingly surrendering freedom for comfort.

These concerns reverberate today in digital politics, where the algorithmic agora has replaced the Athenian one. Political expression is instant, emotional, and public. The influencer, not the philosopher, dictates moral sentiment. “Burn it all down” and “rebuild anew” remain familiar refrains—echoes of revolutions that promised rebirth but often yielded disillusionment.

Section 1: The Psychology of Party Adherence

Identity, Belonging, and Cognitive Closure

Political parties offer not merely a program but a psychological home. As Henri Tajfel and John Turner argued in their Social Identity Theory (1979), individuals derive self-esteem and meaning from their group membership. Loyalty becomes not ideological but existential.

As Nietzsche observed, “Madness is rare in individuals—but in groups, parties, nations, and ages, it is the rule.” Tribal identification transforms political discourse into moral theater: one’s beliefs signal virtue, while dissent becomes betrayal.

George Orwell, in Notes on Nationalism (1945), described this moral intoxication: “Every nationalist is capable of the most flagrant dishonesty, but also—since he is conscious of serving something bigger than himself—he is largely unaware of it.”

Thus, party adherence often provides a narrative of meaning. People do not simply support policies—they defend a worldview that secures their moral and social place in an unstable reality.

The Need for Cognitive Closure

The research of Arie Kruglanski (1996) on the “need for closure” illuminates why ideologies that offer simple answers gain traction in complex times. When threatened—by economic uncertainty, moral relativism, or technological disruption—people seek certainty over truth.

This need explains the appeal of radical political narratives promising purity and coherence. As Dostoevsky wrote in The Devils, “Man has such a predilection for systems and abstract deductions that he is ready to distort the truth intentionally.” Ideology, in this sense, becomes a psychological refuge—a fortress against ambiguity.

Section 2: The Rise of the Digital Prophet — Graham Platner and the Micro-Cult Phenomenon

Digital influencers such as Graham Platner embody the archetype of the disillusioned insider turned prophet. They rise during ideological winters, when movements have cooled into bureaucracy and their followers crave renewal. Platner’s rhetoric—moral, aesthetic, apocalyptic—mirrors a long tradition of charismatic reformers who promise to purify corrupted faiths.

Platner, accused by critics of being a “secret Nazi,” exemplifies how digital personalities become symbolic battlegrounds for projection. His followers see him as a reformer; detractors, as a reactionary threat.

Much like the Sophists of ancient Greece, these influencers operate not as teachers of virtue but as performers of conviction. Socrates, in Gorgias, condemned such figures for selling persuasion rather than wisdom: “They make the weaker argument appear the stronger.”

Similarly, the influencer economy turns ideology into content—a commodity traded for clicks, patronage, and belonging. The result is not a public forum but a marketplace of moral sensation.

Section 3: The “Sharing vs. Owning” Paradigm

A central rhetorical trend in neo-collectivist discourse is the dissolution of ownership—the belief that private property perpetuates inequality and alienation. The new utopia, it seems, is one where everything is shared: homes, incomes, even emotional labor.

But as Edmund Burke warned in Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), “Liberty, when men act in bodies, is power.” When ownership diffuses into abstraction, responsibility follows it into disappearance.

Aristotle foresaw the same pitfall: “When everyone owns everything in common, no one takes responsibility.” Ownership, in its essence, anchors individuality—it binds a person to effort, care, and stewardship.

Modern movements often romanticize communal living while underestimating the psychological cost of detachment. Dependency, even when voluntary, corrodes autonomy. As John Stuart Mill observed, “A state which dwarfs its men, in order that they may be more docile instruments in its hands—even for beneficial purposes—will find that with small men no great thing can really be accomplished.”

Section 4: The Rinse–Wash–Repeat Cycle of Digital Progressivism

The life cycle of modern ideological movements follows a familiar pattern—accelerated by the velocity of social media:

-

Idealism: Visionary energy fuels calls for justice and reform.

-

Institutionalization: Bureaucracy forms, ideals dilute.

-

Disillusionment: Hypocrisy and fatigue emerge.

-

Fragmentation: Purist factions and prophets rise.

-

Renewal or Collapse: Either reinvention occurs—or schism.

This cycle, once stretched across generations, now unfolds within a few viral seasons. The algorithm rewards outrage over wisdom, immediacy over endurance.

Karl Marx wrote that history repeats itself “first as tragedy, then as farce.” In digital politics, it repeats as content. The tragedy lies not in ideology but in its transformation into performance art.

Marshall McLuhan foresaw this shift: “The medium is the message.” What once was a platform for discourse is now a stage for identity projection. Truth competes not with lies, but with spectacle.

Conclusion: Toward a More Grounded Politics

The ancients taught that the strength of a republic lies in balance. Plato cautioned that justice is “doing one’s own work and not meddling with what isn’t one’s own.” Marcus Aurelius reminded us: “Waste no more time arguing about what a good man should be. Be one.”

In the age of Platners and platforms, of moral certainties packaged as viral videos, the challenge is not to feel more strongly—but to think more deeply.

We must resist the seduction of ideological absolutism—the false promise that moral virtue can be achieved through political belonging. As Hannah Arendt observed, “The most radical revolutionary will become a conservative the day after the revolution.”

To build a durable democracy, citizens must rediscover the ancient balance between personal virtue and collective concern—a politics grounded not in the fever of hashtags, but in the humility of human limits.

Bibliography

-

Aristotle. Politics, Nicomachean Ethics.

-

Plato. The Republic, Gorgias.

-

Cicero. De Re Publica, De Legibus.

-

Marcus Aurelius. Meditations.

-

Nietzsche, F. Beyond Good and Evil.

-

Burke, E. Reflections on the Revolution in France.

-

Tocqueville, A. Democracy in America.

-

Orwell, G. Notes on Nationalism.

-

Dostoevsky, F. The Devils.

-

Mill, J.S. On Liberty.

-

Marx, K. The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte.

-

McLuhan, M. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man.

-

Arendt, H. On Revolution.

-

Tajfel, H. & Turner, J.C. (1979). An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict.

-

Kruglanski, A. (1996). Motivated Social Cognition and the Need for Closure.

-

Sunstein, C. (2009). Going to Extremes: How Like Minds Unite and Divide.